Hidden in the valley of Swan is a tiny burg called Irwin. Before moving to Irwin in 1993, the first place I landed in the Rocky Mountains was Jackson Hole, Wyoming, a short distance away. My photography business often took me west and, as with all road trips, the journey home to Jackson seemed to grow exponentially farther as the day grew longer. Whenever I traveled east from Idaho Falls, I’d leave potato land behind, enter the beautiful rolling barley fields of Antelope Flats, and then drop down Conant Hill where, lickity-split, the landscape changed from agricultural ambience to alpine splendor. I’d still be seventy miles from my destination when I descended this grade, but I felt as if I were already home. Home isn’t a house: it is a state of mind. Long ago, my heart had told my mind that home was the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, and Conant Hill dropped me right into it, at Swan Valley. Irwin was just a few miles down the road.

In pre-Columbian times, the Shoshone and Bannock Tribes began spending time in the valley during summer but, clearly wiser than us, they headed to lower elevations at the first storms of autumn. Around 1810, American trappers joined them, but they were preceded by French trappers. Conant Valley, which is actually the northwest end of Swan Valley, was named after trapper Charles Conant. By 1899, the trappers were mostly gone, although there was one still here, named Bill Wolf, who lived at the confluence of Dry Creek and the Snake River. People still trap today but their objective is just to make a few extra bucks while revisiting the past.

The valley is narrow. At the northwest end is a well-appointed cattle ranch and soon the first fishing lodge appears on the bank of the Snake River’s South Fork. You cross the river and the valley opens up into a pleasant mix of homes, farms, and ranches. To the east, the Snake River Range’s Baldy Mountain dominates the landscape, diminishing the taller Mount Baird miles beyond it. To the south, the Caribou Range owns the skyline, a fine string of alpine splendor with no peak trying to outdo the others.

The town of Swan Valley is at the junction of Highways 26 and 31. Its heart is a nice cluster of businesses where people can fill their ice chests, grab a meal, a room, or just enjoy an ice cream cone. Those who go north on Highway 31 will wind their way toward Victor, a short journey that passes a series of rolling hills, barley fields, and cattle to end at Pine Creek Canyon, where access to the Big Hole Mountains begins. Those who continue south from the town of Swan Valley will soon arrive in Irwin.

A few prospectors found a bit of gold in the valley but not enough to stake claims. In 1885, prospector Joseph Irwin claimed to have found some decent gold up Falls Creek, but it was thought this was an investment scam. Irwin’s declaration seemed believable enough, since there had been a rich gold strike on Caribou Mountain forty miles away, the likely source of the fine-grained “flour gold” placer in the river.

Before settlers arrived and homesteading commenced, the valley was free range, used for summer grazing by open-range ranchers, rustlers, and horse thieves. Around 1879, two open-rangers named Charles and George Ross kept a couple hundred horses of questionable origin in the valley, as did the Irwin brothers. They all left after the valley was homesteaded, likely cussing the homesteaders as squatters.

The Irwin Post Office, the school, a cluster of homes, a fly shop, a medical clinic, and hair salon are in Irwin, about four miles from Swan Valley, and then in the blink of an eye, the landscape is rural again, until you get to the Palisades section part of Irwin, which has a convenience store, a fishing lodge, and an odds-and-ends shop. This south end of the valley hosts Palisades Reservoir, the biggest attraction of Irwin.

There is debate about who Irwin was named after. Some say it was the 1880s prospector Joseph Irwin, who is said to have squatted here. But I think it was more likely named after a man named Charles Irwin, because he was a friend of Willard Weeks, who laid out the town.

Irwin’s posted population is 108, but it really isn’t much more than a suburb of the adjoining municipality of bustling Swan Valley, whose population is 240. The greater Swan Valley’s population is estimated at around seven hundred (see IDAHO magazine, October 2012, “Podunk Perfect: The Swan Valley Life”). I have always thought it was a waste of government money not to share a post office because of the valley’s paucity of people, although I’m thrilled to not be a part of the neighboring municipality’s more restrictive building & septic mandates. [Daryl, what mandates do you mean?] We prefer our metropolises small around here. Few have ever heard of Irwin, so when telling anyone were I live, I just say Swan Valley, as this beautiful valley is known by many.

I’m a newcomer to the valley, since I've been here only since being priced out of the Beverly Hills of Wyoming more than a quarter-century ago. Some say you will never be a local unless you were born here. By this standard, one of my sons is a local and the rest of the family is not. But most folks are welcoming, so long as you don’t join the city council and try to change the place into the one you left behind.

The first homesteaders, Charles Dixon and Charles and Joseph Higham, arrived around 1883. Dixon moved here from mining operations in Colorado, where he witnessed the shooting of John Ford, who killed Jesse James. While Dixon was trying to get his homestead up and running, he worked for the Ross brothers before they departed. The Higham brothers and William Hyde built the first ferry in 1885, when the first sawmill was started. The valley was ready to grow.

Many of the early homesteaders didn’t make it and moved on. Sam Weeks arrived in 1891, and there seem to be four Weeks clans in the valley now, all claiming not to be related to the other. It sounds unlikely but I’ll take their word for it. Area resident Trellis Fleming’s family, the Denials, arrived in 1891. Her husband Larry’s family showed up in 1903. Today, Larry is the valley’s historian, and he helped guide me through its history. A few families who who arrived early and whose descendants are still around include: the Jacobsons, Weeks, Ricks, Traughbers, Hincks, Cromwells, Lundquists, Highams, Winterfields, and Kopps.

The community is evolving, as are all pretty mountain valleys of the West. Most people here work fifty miles away in Idaho Falls or sixty miles away in Jackson Hole. A lucky few have carved a niche in tourism or the growing construction industry, building homes for blue-collar commuters or luxury homes by the river or on the hilltop. Some write code and email it to Silicon Valley, or trade stocks until 2 p.m., when the market closes, and then go fishing for the rest of the day. There is a growing retirement community who came here to fish and found a place they felt compelled to retire in.

Much is different from when Robert Oakden, a prolific log home craftsman and miller, was the first postmaster in 1894. He always seemed to be selling his last homestead for a new one to build and then sell.

The first Mormons to homestead were the Michael Yeaman family in 1890. Many soon followed as the religion grew and expanded both north and south of Salt Lake Valley. The first ward was established in 1893. Today, half the valley’s populace is Mormon. A large LDS church was built but in 1948, but I was horrified to stand among other townsfolks in 2015 and watch this structure of so many memories burn to the ground, even as some remembered their fathers who had helped to build it. A bigger one has taken its place, and I’ll wager it won’t be long before this one has the heart the other one had. Since the valley’s beginning, people of other denominations met at town halls and schools to worship, until the Chapel in the Valley was built in 1966.

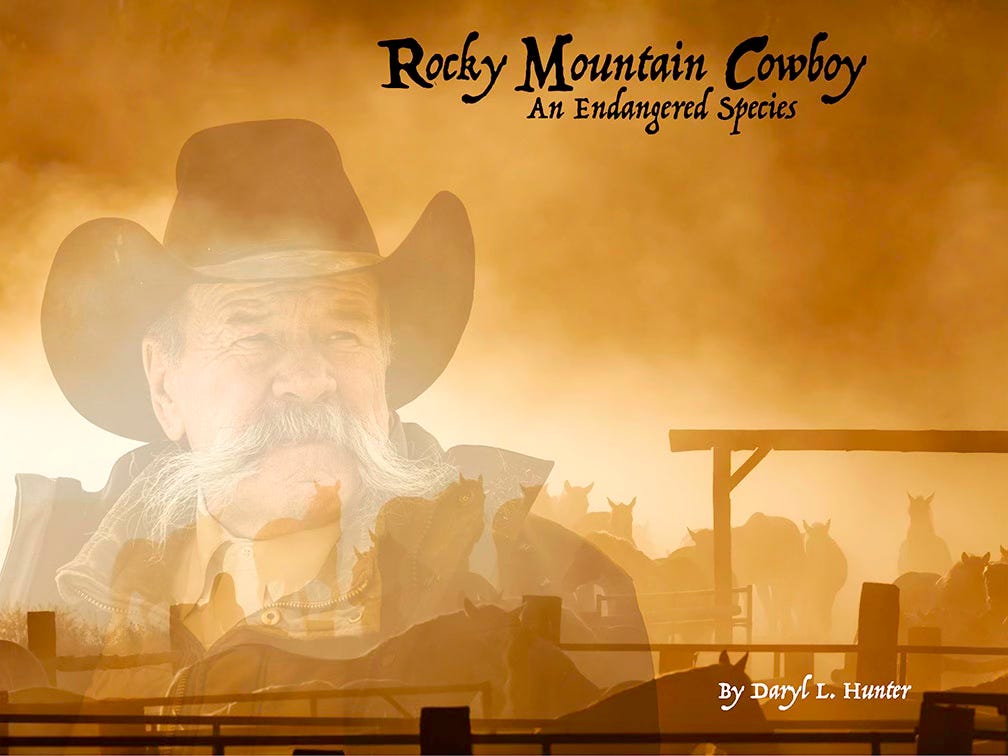

The ranching and farming heritage is still alive and well in Swan Valley. The local cowboys and farmers often double as fishing or hunting guides, because working the land can fall short of profitable. The closest city, Idaho Falls, had the highest percentage of PhDs of any population center in the nation when the nearby Idaho National Laboratory was established, which built the nation’s first nuclear power plant. Many INL employees have chosen to live in this mountain valley instead of the grain and potato fields of Idaho Falls. The valley is quite the eclectic socio-economic stew, where titans of industry mix comfortably with trout bums and commuters, and we all become friends.

Palisades Reservoir nestles between the Snake River Range and the Caribou Range. Formed by Palisades Dam, which was started in 1953 and completed in 1957, it is one of the largest earth dams ever built in the USA. They say it is impossible to break, and I often hope they are right. The lake is eighteen miles long and when full covers 16,100 acres, with seventy miles of limited-access shoreline. It backs up water all the way to the three-way confluence of the Snake, Greys, and Salt Rivers in Alpine, Wyoming. The building of the dam changed the character of the valley. Many construction workers moved here, and businesses sprouted up and thrived until a given job was over, which is why today there are still skeleton remains of many buildings around Irwin. The acres of water displaced dozens of farms and ranches in an area known as Grand Valley—and that’s a lot of people for one community to lose. Some relocated in the valley, while some moved on.

For decades. Swan Valley’s South Fork of the Snake River was a secret fly-fisherman’s nirvana. The lunker brown trout population and the uncommonly large cutthroat trout were only whispered about, from one aficionado to another. And then, much to the chagrin of the locals, a fly-fishing outfitter whispered it rather loudly to a fly-fishing magazine, and the fly-fishing outfitters blossomed like dandelions on a warm spring day. Idaho Fish and Game soon had to limit the daily allowance of outfitters’ permits and guides. The legendary lunkers disappeared. But every sword is double-edged: the demise of the lunkers was balanced by new jobs in the valley.

Fly-fishing’s popularity was exacerbated upon the release of the movie, A River Runs Through It. Thousands made reservations on fly-fishing rivers all over the West, apparently so they could look like Brad Pitt casting to the far side of the river for trout that couldn’t be hooked, because forty yards of line has too much slack to set a hook—even if it were possible to see a trout take a fly at that distance. No matter: cinematic magic was made and unrealistic expectations were created. Still, the fishing here remains excellent by today’s standards compared to elsewhere. On my first visit to the river’s edge, in no time at all I had a writhing three-pound rainbow tail-dancing across an eddy, as it tried for the fast water a short distance away. Ah, ha! I had heard the South Fork was a better fishery than Jackson Hole’s upper Snake, but had never bothered to try it. The fish wasn’t the only one hooked. For the next four years, I was a fly-fishing addict. And I joined the army of fly-fishing guides.

The South Fork is said to be the third best trout fishery in the Lower Forty-Eight, after the Bighorn in Montana and the second-place Green River at Flaming Gorge, Utah. One superlative the South Fork can claim is as the best “wild trout” fishery in the Lower Forty-Eight. All its fish spawn in the mountains, whereas most of the fish in the Bighorn and Green are hatchery fish, which don’t fight as well. Superlatives are subjective, but the outfitters around here stand by this one.

As a beneficiary of attention deficit disorder, one of my many bifurcations of interest has been horses. On horseback, I’ve explored deep in the mountains surrounding the valley, all of which have streams flush with fish. This is where the trout of the South Fork spawn, a heaven on earth for the hunter, trailrider, and hiker. Lacking the fame of the nearby Teton Range, these mountains offer many trails you can have nearly to yourself, and I love this alpine solitude. In the last decade, grizzlies have been repopulating the Snake River Range, while wolves have repopulated all the surrounding mountains. I bumped into my first Snake River Range grizzly up there in 2011 (which is why I always pack bear spray).

Autumn in Swan Valley has a splash of color many mountain valleys lack, and that is because of this region's mountain maple. Although not much of a tree, during autumn the mountain maple lights up in that indescribable glowing burgundy, crimson and scarlet, like its cousins in the eastern U.S. When we’re lucky, the mountain maple’s color change overlaps with that of the golden aspens, which usually change a bit later. During a perfect autumn, the mountain maples are red when the aspens are gold, and the reservoir is accented by a light early snow.

Like nearly every mountain range in Idaho, the Big Hole Mountains, the Snake River Range, and the Caribou Mountains that crown the valley views from Irwin are prodigious hunting grounds. These mountains have been providing meat for the region for a century and a half, and a few outfitters make their living out of them with hunting trips in the autumn and pack trips in the summer.

Within fifteen minutes of my home, I can launch a drift boat on the river, a ski boat on the lake, or be at any number of fantastic trailheads. In winter, we have four ski resorts within an hour’s drive. But I can imagine our rural setting didn’t help in certain domestic scenarios. Plenty of times, a man who tried the river’s world-class fishing must have decided this was the place for him and started shopping for real estate. After finding the place of his dreams, he would have brought his wife to Idaho. When she had a good look around, her response may well have been, “What a fantastic place (no pause) where’s the grocery store?” His reply: “There’s a good one twenty-five miles to the south, a better one thirty miles north, and a superstore fifty miles to the northwest.” And that would have been the death of many a fisherman’s dreams.

When I first drove though the valley in 1986, I not only marveled at the beauty of this wide spot in the road but wondered why it was so run down, with so many relics from the temporary population boom when Palisades Dam was built. After years of reflection, and after watching what happens to so many places after they get “discovered,” I’ve come to realize that maybe leaving a place a little run down—or doing zoning that takes into consideration the working man and his grandchildren—can be a wise thing. I’ve lived in many resort towns and am attracted to them when they’re small, quaint, and undiscovered. But it usually isn't long before word spreads about the town as the “next great place.” In my experience, for a town to become the next great place can cost the community its heart and soul. I have come to dread new gingerbread buildings, and to value the relics of yesteryear.

Others will disagree, but I’m sad that a small grocery store is being built in the valley by a friend of mine. I’ve always believed that my twenty-five-mile drive to the store along the Palisades Lake shore beneath the Caribou Mountains and the Snake River Range was a small but beautiful penance to pay for the elbowroom of nowhereville. On the other hand, I don’t begrudge my friend for facilitating the inevitable—better a founding family than someone else.

I guess what it comes down to is I fail to understand why anyone chooses to live in a city over a smaller community. But I’m glad most do.