Eleutheromania: The Pursuit of Freedom

Eleutheromania, derived from the Greek words eleutheria (freedom) and mania (obsession), describes an intense, almost insatiable desire for freedom.

By Daryl L. Hunter

Words are wonderful things. As a hack writer, I’m always seeking new ways to convey our lexicon through clever phrases. One day, I stumbled upon the word "Eleutheromania". The light turned on as I realized I was an Eleutheromaniac.

Eleutheromania, derived from the Greek words eleutheria (freedom) and mania (obsession), describes an intense, almost insatiable desire for freedom. This concept transcends mere preference, embodying a profound psychological and philosophical yearning for autonomy, self-expression, and liberation from constraints—whether societal, personal, or existential. In a world increasingly defined by structure and obligation, eleutheromania resonates as both a personal drive and a cultural phenomenon, inspiring individuals to challenge norms and seek unbound existence.

How did I arrive at this point? I grew up with the freedom of being largely a latchkey child, though it came with some complications. Hailing from a broken home, I am proud of my mom, who left her alcoholic and abusive husband. Although my mom struggled with alcoholism, she managed to achieve sobriety through AA, earned her GED, and later attended college. Her departure from my father enabled her to thrive. When she wasn’t focused on her studies, she was busy climbing the social ladder or the ranks of AA. Many alcoholics tend to be social individuals, often driven by a sense of narcissism. My mom cherished sharing her triumphs in overcoming her challenges, but her commitments to school and AA left little time for family life. My little brother and I were okay with that; we enjoyed a largely parent-free childhood in a small town, with beautiful fish ponds, mountains to explore, and a wonderful neighborhood full of kids, creating joyful memories before our teenage years.

At its core, eleutheromania reflects a universal human impulse. From historical figures like Thomas Jefferson and Nelson Mandela, who fought against apartheid, to John Locke, Samuel Adams, and Alexander Hamilton, who instituted freedom from King George, as well as Martin Luther, who challenged the Catholic Church’s monopoly on theology, the craving for freedom manifests in diverse ways. It fuels revolutions, artistic movements, and personal transformations. For some, it’s the rejection of societal expectations—choosing unconventional careers or relationships. For others, it’s physical, like exploring uncharted territories, or intellectual, like pursuing knowledge free from dogma. As a photographer, activist, interpretive guide, photo workshop teacher, writer, and wanderer, I seem to check off a few of the above.

My mother learned about the pitfalls of latchkey kids when my older brothers, who were seven and nine years older than me, were teenagers. On my thirteenth birthday, she decided to crack down and remove the freedoms I had come to know. Her statement: “how sad you are now a teenager; you were such a nice boy.” Of course, I rebelled and was deemed incorrigible. The crime of incorrigible landed me in an ultra-restrictive foster home that robbed me of the freedom of movement and social engagement in school. I went into foster care an extrovert and came out an introvert—an introvert that experienced great deprivations of freedom.

Eleutheromania doesn’t always demand grand gestures as Martin Luther and our founders did; it can be as subtle as carving out moments of solitude in a hectic world. Nature photography is my therapy, as were dog mushing, horseback trail riding, and fly-fishing. All were my therapy from this hectic world. However, this obsession with freedom comes with complexities. The pursuit of absolute autonomy can lead to isolation or impracticality. Societies function on interdependence, and unchecked eleutheromania might strain relationships or responsibilities; yet, I argue it brings balance to the power structure; government is a magnet for the megalomaniac. Philosophers like Jean-Paul Sartre have explored freedom’s burden, noting that with liberation comes the weight of self-responsibility. The eleutheromaniac must navigate this paradox: the desire for freedom versus the reality of human connection and consequence. Consequently, against my inner will, I got married— the most antithetical action against Eleutheromania of all.

At the end of my sixteenth year, I got the foster home shut down with the argument; “Sure we aren’t offending, not because you know we are rehabilitated, but because we are allowed nor rope to hang ourselves. Without the freedom of movement, how would they know? Upon the return to my mom, she gave up the battle of restricting my freedom.

By eighteen, I discovered my itchy feet; I wanted to see things, go places, and make up for lost time. For the next dozen years, I chased my whims across California and Alaska, eventually ending up in Wyoming. Although I was never a hippie, I shared their rejection of societal norms and their love of nature. While I’d spend short amounts of time in the city to make money, I would soon escape to live at the beaches of southern and central California, the redwoods of northern California, or the mountaintops of the Los Angeles National Forest. Forest and wilderness represented freedom. Creatures of cities more easily adapt to the dictates of the powers that be; the more rural you get, the less that is the case.

Ultimately, eleutheromania is a dynamic force, driving humanity toward growth and self-discovery. It challenges us to balance personal freedom with collective harmony, to seek liberation without losing purpose. In embracing this mania, we honor the human spirit’s relentless quest to be free. Natural Law’s foundation in Eleutheromania. Natural Law is a philosophical and legal theory positing that certain universal, objective moral principles and rights are inherent in human nature and the natural order, discoverable through reason, independent of human-made laws. It suggests that these principles govern human behavior and justice, transcending cultural, temporal, or legislative boundaries. Natural law was a guiding principle of our founders.

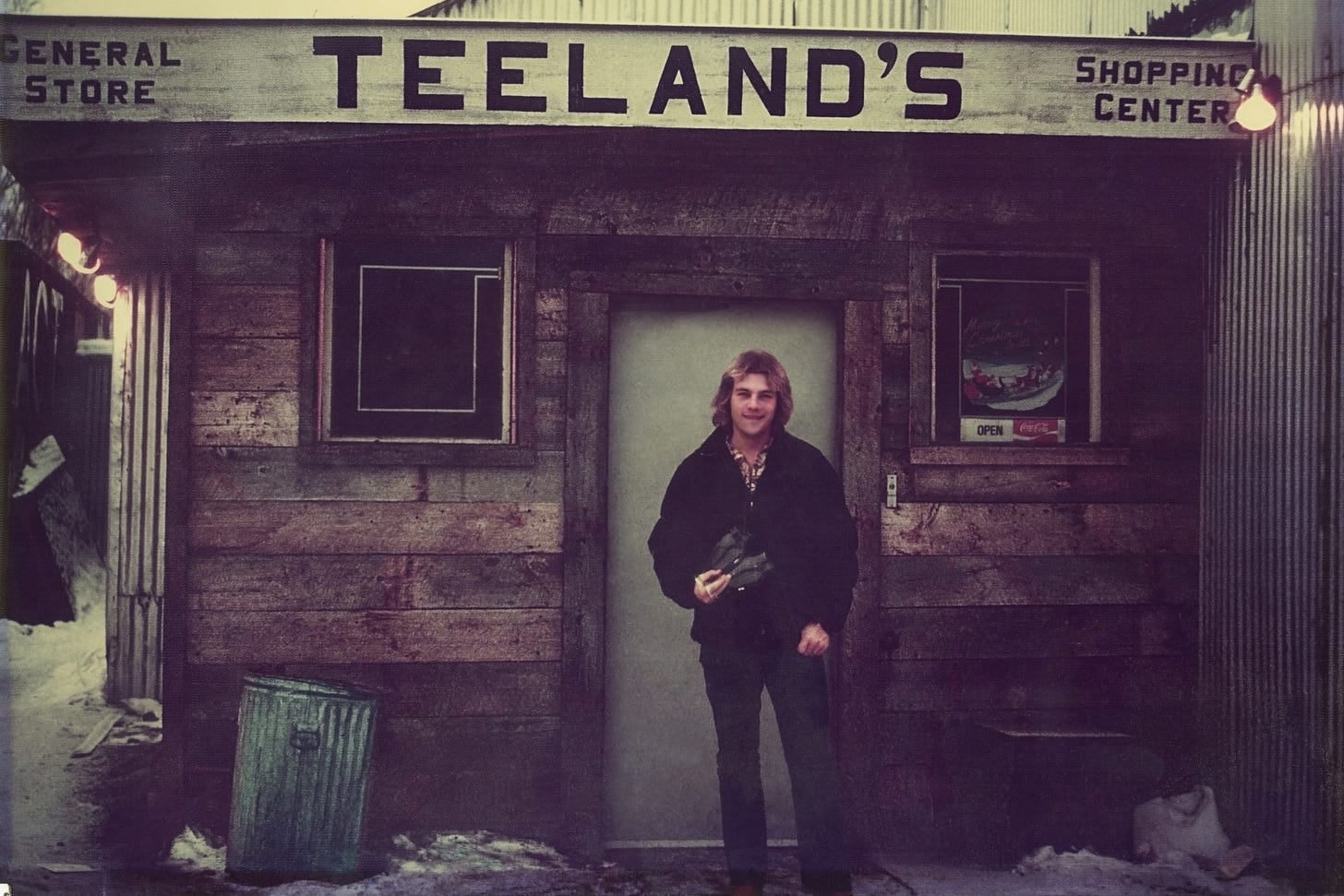

In Alaska, I became a dog musher. My friends were the homesteaders who had escaped to Alaska for the ultimate freedom, and I quickly adopted their mindset, even though I already had a significant head start on that. Dang, I miss that feeling of heading off into the great unfenced wilderness of Alaska with my dog team. While there, this latchkey kid found myself working on the Alaska Pipeline, a high-paying job that attracted risk-taking dreamers from across the country. Most were there to finance their entrepreneurial dreams. Entrepreneurs are free from the dictates of business owners; I was inspired and motivated by something I never got in my broken home: motivation and the dream of opportunity.

An economic crash in 1979 ended my lessons in the Alaskan bush and my boomtown dreams, forcing me to move back to California. There, I applied my dyslexia and lack of formal education to entrepreneurship through trial and error, eventually succeeding, only to find that success can be a straitjacket of its own. This kid who grew up on welfare learned that a prodigious income wasn’t all that I imagined it would be. Obligations piled up, and even ambitions became a burden on freedom.

From my latchkey foundation and hometown on the beautiful Central Coast of California, I developed a love for nature and was always traveling to cool, beautiful places. After years of vacillation, I finally bought the camera I had procrastinated on getting so I could document the amazing places I saw. I had gotten into real estate in Southern California, and the more landscape shots I took of the Sierra Nevada and coastal California, the less I wanted to be in the LA metro. So, I dumped my business and all its baggage and moved to Jackson Hole, Wyoming where the Grand Tetons and Yellowstone beckoned.

In Jackson Hole, I rented a log cabin on a ranch. My education on pioneer life began, actually very similar to the homesteader sourdoughs of Alaska. Rural people are Eleutheromaniacs like me, but trained through generations. Both in Alaska and Wyoming, I learned rednecks aren’t the troglodytes they are made out to be by those who grew up on cement. Charlie Daniels once sang; “A Country Boy Can Survive.” Because they are as free as possible and independent by necessity, they develop multiple skill sets that are unattainable in a university. Horse sense and common sense are the result. Life on the ranch resembled that in Alaska; it was on the edge of a designated wilderness that I continually explored on horseback. This section of the wilderness lacked public access, so I enjoyed thousands of acres all to myself. Like running the dog team, it provided an amazing retro ambiance reminiscent of the Eleutheromaniac pioneers. These sons of the pioneers have had independence and self-sufficiency inculcated into them by birth and by culture. I am fortunate to call many of them my friends. To say I wasn’t inspired by my sourdough, ranchers, Mentos, and friends would be a significant omission.

In Alaska, I was inspired by the complete lack of building regulations; you could construct your home out of your pocket as you could afford it, without the government dictating your every move and profiting off every permit. You could provide a roof over your family’s head unencumbered by a mortgage. Conversely, in California's real estate and construction, you always had a man with a clipboard as your shadow and pickpocket. Is my revolution showing?

My eleutheromania evolved into activism and letters to the editor, which led to a website outlining the evils of governments and then to freelance writing; the proverbial thread of knowledge had been pulled, and there was no end to it. Everyone needs freedom, whether those who grew up on cement know it or not.

The proverbial thread of no end led me to explore contemporary conservative thinkers who passionately revere the intellectual brilliance and foundational ideals of the founders of the United States. These individuals frequently engage in discussions and teachings about the principles, writings, and philosophies of these historical figures, emphasizing their relevance in current societal and political contexts.

Imagine a day before television when your evenings could be devoted to reading the wisdom and foibles of philosophers such as Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, and Polybius, along with politicians from Greece, Rome, and the Magna Carta. Enlightenment thinkers and proponents of classical philosophy, such as David Hume, Adam Smith, and Francis Hutcheson of the Scottish Enlightenment, significantly influenced economic and moral philosophy. Hutcheson’s ideas on moral sense and the pursuit of happiness likely shaped Jefferson’s phrasing in the Declaration of Independence. The founders also read revolutionary pamphlets like Thomas Paine’s Common Sense (1776), which synthesized Enlightenment ideas into a call for independence, and James Otis’ The Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved (1764), which argued against taxation without representation, by kerosene lamp or candle, free from distractions a nation was born.

Today, the left is a panoply of the unhinged who complain that the right keeps moving farther right. I argue that four decades ago, before the wealth of new media, conservatives were conservative by nature, not by education. Today, education rains down on us from radio, podcasts, and other platforms. Pundits elucidate where we may want to investigate to elaborate on the lesson of the day. This often relates to the Constitution, those who created it, and why. The result is that we have gone so far right we have fallen off the cliff into classic liberalism inspired by our founders.

This experience of reading my kerosene lamp is very close to my heart and memory because, in Alaska, all I had after dark was a kerosene lamp. But silly me, instead of reading enlightenment, I was reading entertainment like Robert Ludlum's spy adventures, which taught me about Europe. James A. Michener, James Clavell, Herman Wouk, and Edward Rutherfurd taught me about the world. Alan Eckart introduced me to the settling of the eastern frontier, while others educated me on the mountain men, Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull, and other notables of the West. This poorly crafted point signifies that without modern distractions, engaging in intellectual pursuits was a fruitful way to spend a dark evening.

Currently, I live in a modest, mortgage-free home situated in an unincorporated area of the Greater Yellowstone Region, without a homeowners association. My only monthly utility is electricity, sourced from a nearby dam that provides the most affordable electricity in the USA. I often think about how I wish I could have afforded a solar system, which would have allowed me to be completely self-sufficient apart from the property tax; however, I have done better than most. Reflecting on my journey from the freedoms of being a latchkey kid to sharing insights gained from the scholars of eleutheromania brings me joy as an insatiably curious individual. Now that is about as close to eleutheromania nirvana as one could manage and still remain married.